South side, as reflected in a California Scrub Jay’s eye:

South side, as reflected in a California Scrub Jay’s eye:

On our trip to the Big Island last July, Hai showed us a beautiful Marbled Shrimp tucked into a cauliflower coral on one of the pilings in (where else?) Kawaihae Harbor. It was a female. The shrimp was still there on our recent return to the island, and it had been joined by another one, also female.

On the February trip, Wendy showed us where another Marbled Shrimp had taken up residence along the quay at Mahukona. This one was male. Wendy said she’d seen other Marbled Shrimp at this site, all male.

And now for some martini-fueled rambling:

It’s tempting to think that Marbled Shrimp generally tend to live in single-sex domiciles. One could invoke the law of small numbers to verify this if only there were a law of small numbers. There is not; there is only a law of large numbers. This statistical law basically states that if you flip a coin one thousand times you will get very nearly fifty percent heads and fifty percent tails. If not, you can conclude that the coin has been tampered with. But since there is no law of small numbers, five heads up coin tosses in a row mean nothing. And two same-sex Marbled Shrimp homes also mean nothing.

Irrational species that we are, we tend to believe in the law of small numbers. You see it all the time: “Two of my friends got the vaccine and they both got sick.” The result is that many of us embrace untruths, guided more by what we feel than what we know.

The difference between small and large number is not necessarily clear though. There are statistical tools for this, but there’s always a bit of subjectivity involved because you need to decide how sure you want to be. Very sure needs a much larger number of observations than just a little sure.

Anyway, maybe, just maybe, despite its biological unlikeliness, Marbled Shrimp actually do live sexually segregated lives, at least when they’re not reproducing. As lots of research papers (including a couple of mine) conclude: further study is needed.

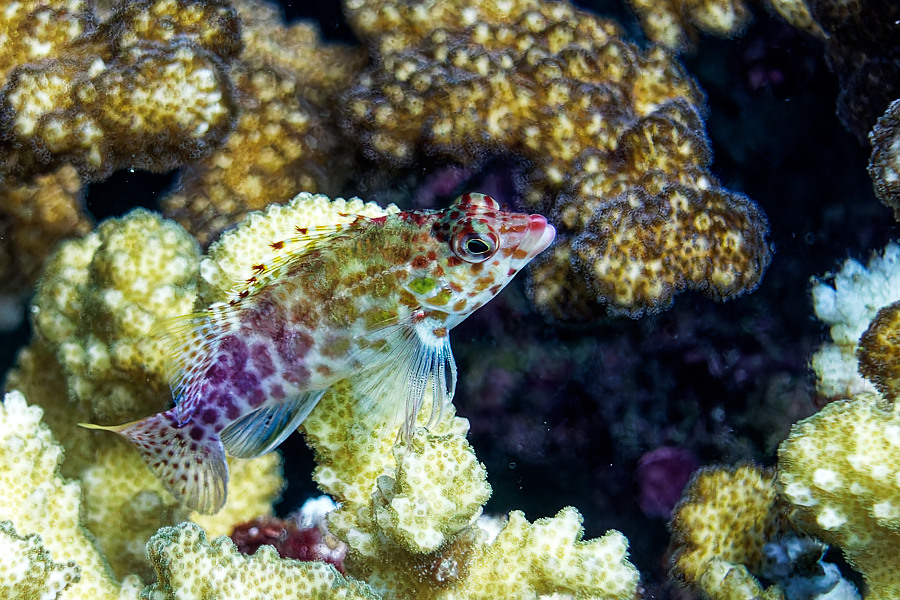

We’re back in Hawaii for a couple of weeks. I’ve gotten into the water a handful of times, both snorkeling and diving. There are still lots of fish on the Kohala reefs, but they don’t seem quite as abundant or diverse as last time we were here in July. It seems that way every time we come here—fewer and fewer fish. Marla and many of our friends share this perception. But, with the exception of the aftermath of the devastating 2015 coral bleaching event, the decline has been fairly subtle and inconsistent. Maybe populations are indeed declining, or maybe it’s just a tendency to recall the past as better than it actually was. I hope it’s the latter.

There’s still plenty to see and photograph though.

Winter, such as it is here on the mild, frost-free Central Coast, means birds, birds, birds. Migrants of all sorts are down from their breeding grounds up north, and even the year-round resident species seem more abundant than in the warmer months.

There’s also the upcoming weekend’s Morro Bay Winter Bird Festival. Not the kind where people dress up as birds and flap their arms, the other kind. This one involves four days of birding field trips and lectures. It’s a big deal, supposedly the largest such event in the country, with many of the nation’s top bird authorities in attendance. Marla and I plan to spend a lot of time there, including some volunteer organizing.

Anyway, I thought I’d post a few recent bird shots in recognition of the Festival and of the new year. None of these birds are rare, or even uncommon. Just beautiful.

Our trip to Cabo Pulmo was the first time we’d dived in the tropical East Pacific. A lot of the fish we saw resembled those we’d seen in Hawaii, Bali, and Samoa, but were just a bit different. Due to the vast, mostly islandless expanse of the tropical Pacific east of the 130th meridian the west coast of the tropical Americas is biogeographically distinct from the Central and West Pacific, so fishwatching in Cabo Pulmo left us feeling like beginners. Fortunately, the Smithsonian Institute offers a free app describing over a thousand East Pacific fish species. It’s aptly named Fishes: East Pacific. I don’t know how we’d have begun to identify the fish we saw without this comprehensive guide.

I started diving in the Florida Keys in the early eighties. There were a lot of fish there at the time, but not all that many large ones. The old-timers would tell me “you should have been here twenty years ago.” Fishing pressure had reduced numbers and average size. In the nineties I had the chance to dive in Curaçao. I was excited—my first dive in the Caribbean—there had to be lots of great fish, including lots of big ones. Well, not quite what I’d expected. Once again, I was told I should have been there decades ago. Since then we’ve done a lot of diving and snorkeling in Hawaii, Samoa, and Bali. We were always told the same story—it was way better years ago.

The other week Marla and I dove in Cabo Pulmo, about sixty miles northeast of Cabo San Lucas on the Sea of Cortez*. This time it was a different story. It was made clear to us that there were far fewer fish there in the past. The reason: Cabo Pulmo was designated a Mexican National Marine Park in 1995. The region had been seriously overfished in the past, but fishing of any sort has been prohibited since the National Park designation. Fish have responded accordingly, both with respect to abundance and average size. Cabo Pulmo provided some of the best diving we’ve ever had.

* Mexico has just moved to change the name from Sea of Cortez to Gulf of California because Cortez was not a nice man.

Stumbled across some leftover photos from our July Hawaii trip:

They’re beautiful, weird, and ubiquitous on tropical Pacific reefs. We see Longnose Butterflyfish wandering nonchalantly over the reefs on pretty much every one of our snorkel and dive outings. There are two species that go by the name Longnose Butterfly: the common Forcipiger flavissimus and the somewhat uncommon F. longirostris. John Hoover (hawaiisfishes.com) calls flavissimus Common Longnose Butterflyfish and refers to longirostris as Big Longnose Butterflyfish. Other authorities, such as Keoki Stender (marinelifephotography.com), refer to the respective species as Forcepsfish and Longnose Butterflyfish. Flavissimus is also sometimes called Yellow Longnose Butterflyfish and longirostris is sometimes called Big Forcepsfish. Confusing to you? Me too. Do you care? Well, I do.

Besides being inconsistently named, the two species can be difficult to tell apart. Longirostris tends to be a bit bigger, with a longer snout, but there’s some overlap in size. Two features are generally used to distinguish the species in the field. The first is coloration: I usually look for tiny black dots on the fish’s chest—longirostris has them, flavissimus doesn’t. Trouble is, you have to be close and have good eyesight (and a non-fogged mask) to see this. The second is mouth shape: Flavissimus is supposed to have a deeper oral cleft than longirostris, but I can’t tell the difference, at least not on a living, moving fish. Photos make it a little easier. Like these:

These two very similar species share the same habitat throughout much of the Indopacific, but they don’t directly compete. Flavissimus is a dietary generalist, eating all sorts of small invertebrates, and, rather oddly, often plucking off the tube feet of echinoderms such as urchins and sea stars. (The echinoderms have plenty of feet to spare, but it still sounds painful.) Longirostris on the other hand specializes in picking tiny shrimp from deep inside coral heads.

Anyway, there’s your fish minutiae for the day.

Fall is here and the migrating warblers have arrived in our backyard. More accomplished birders have been reporting their arrival for a few weeks, but we dilettantes have only begun seeing them this week. Several warbler species migrate here each fall from their breeding grounds in the northern coniferous forests. Many stay through the winter, while others continue south into Mexico and beyond. The three species shown below are frequent visitors to our backyard.

When I was a kid I owned several volumes of the Peterson’s Field Guide series—birds, reptiles and amphibians, butterflies, insects, and mammals—to identify any new species of animal I’d come across. Back then they were the gold standard for identifying animals in the field. I used them all, but I used the mammal book least. That’s because I’d only ever see a handful of mammalian species: the usual suspects—Whitetail Deer, Raccoons, Cottontail Rabbits, Gray Squirrels, Eastern Chipmunks, Striped Skunks, Opossums. Sometimes a Woodchuck, and on rare occasions maybe a Red Fox. No need for a book to ID any of those. The part of New Jersey where I grew up also had a large number of small, not so easy to identify mammals—rodents, shrews, moles, weasels—that, despite spending a lot of time in the woods, meadows, and wetlands, I never encountered. That’s the trouble with mammals: most of the smaller ones are secretive and/or nocturnal, while the big ones are wary and, in New Jersey, absent. Nonetheless, I’d sometimes pore over the mammals field guide and dream of one day seeing a shrew, or maybe even a weasel.

Up until the other day I’d never seen a weasel in the wild, nor did I expect I ever would. But on a recent afternoon Marla and I were taking one of our usual walks on Bluffs Trail in Montaná de Oro State Park when we heard a conspicuous rustling in the grass about thirty feet off the trail. We looked over and there was a weasel looking back at us. The gorgeous little animal spent about a minute regarding us with great curiosity before retreating into its burrow.

When we got home I went straight to the web to figure out what kind of weasel we’d seen (it’s the 21st century after all), and learned that it was a Long-tailed Weasel. (There are four species of weasel in the US—Long-tailed, Short-tailed, Least, and Blackfooted Ferret—but it turns out only the Long-tailed is found in this part of California.) Then I pulled my sixty year old copy of Peterson’s from the shelf. All of the series have checklists in the back where the reader can check off the species that they’ve observed. With satisfaction I checked Long-tailed Weasel, the first new mammal species I’d seen in years. The afterglow lasted for days.

As I’ve noted in previous posts, taxonomists have a way of confounding us old guys. I’ve always known the Long-tailed Weasel as Mustela frenata. But that’s apparently not good enough for those taxonomist busybodies. Now it’s Neogale frenata, which in this curmudgeon’s opinion doesn’t have as nice a ring. Oh well, gotta change with the times I guess..

We saw a couple of noteworthy nudibranch (or if you prefer, sea slug) events on our recent trip. Kawaihae Harbor of course.

I’m far from alone in my fascination with nudibranchs—the web is full of nudi fanciers. A lot of it is the phantasmagoria of colors and color schemes, but to me it’s also the hostile, alien environment these little slugs inhabit. They go about their colorful, sluggish business in a world full of stinging hydroids and poisonous sponges (both of which the nudibranchs eat), noxious bristle-worms, and sundry other unlikely creatures. Someone please pass the mushrooms…wait, no need.